.

This is Part II of my commentary on Stephen Senn’s guest post, Be Careful What You Wish For. In this follow-up, I take up two topics:

(1) A terminological point raised in the comments to Part I, and

(2) A broader concern about how a popular reform movement reinforces precisely the mistaken construal Senn warns against.

But first, a question—are we listening? Because what underlies what Senn is saying is subtle, and yet what’s at stake is quite important for today’s statistical controversies. It’s not just a matter of which of four common construals is most apt for the population effect we wish to have high power to detect.[1] As I hear Senn, he’s also flagging a misunderstanding that allows some statistical reformers to (wrongly) dictate what statistical significance testers “wish” for in the first place.

Topic (1). Terminological point. Senn and I had an exchange on it in the comments to Part I. In Senn’s comment, he replied to my last post: “I agree with your interpretation and elaboration of what I wrote.“ That’s a relief! However, he does not think any terminological changes are needed. Perhaps not, but let me explain what I had in mind in my reply to Senn, and then move on to why I said we “are not done” with his discussion.

My Upshot of Senn (from Part I). The gist of Senn’s guest post is this: By defining a clinically relevant observed D “for judging practically the acceptability of a trial result” –D*–, the critical value for statistical significance, then our test is highly capable of yielding statistical significance D* when the underlying parametric discrepancy ∆ is one we would be very unhappy to miss– δ4. You can also get your wish of being happy to find a D that is just statistically significant, that is, you can be happy to observe D*. That’s because D* accomplishes the twin goals of statistical significance tests. δ4 was set at 1, and the power to detect ∆ = 1 is set at .8.

(Recall I’m using ∆ for population or parametric differences, what I call discrepancies, and D for observed differences, or values of the test statistic.) The terminological issue, or possible one, is this: Tracing out Senn’s remarks and terminology, much of it in bold in the blogpost, we end up saying both:

(a) D* is not a clinically relevant difference (∆), that is, it is smaller than δ4.

(b) D* is a clinically relevant difference (D) “for judging practically the acceptability of a (statistically significant) trial result”.

Once again: D* is the critical value just reaching statistical significance that also results in a .8 power to detect the clinically relevant ∆, δ4.

That dual usage of “clinically relevant” in describing both D* and δ4 is fine if handled carefully—but listen to how it might sound. It could be confusing (even if one emphasizes that the first refers to an observed difference, and the second to a parametric or population difference). In addition, construing a (just) statistically significant difference as clinically relevant might make it sound as if it’s evidence for a clinically relevant discrepancy, whereas, as Senn notes several times in his guest post, it would only be good evidence that the underlying discrepancy exceeds the lower confidence bound (set at a reasonably high level). This is assuming a just statistically significant difference is observed.

In the comments to my last post, I proposed modifying terms, but since we’d want to make the same point in examples outside of clinical trials, “clinically” needn’t even be used. Perhaps δ4 (in this example, set to 1) could be called “the highly relevant (population) discrepancy” Then D* could be called (something like) “the practically relevant observed difference D*”. This might also help ward off any supposition that statistical significance tests are well represented as comparing 0 effect size to a highly relevant population effect size (topic (2) of this post). I invite recommendations from readers.

Since Senn agrees with my summary of his post, but sees no reason for any terminological changes, I think he intends only that the tester recognize the relevance of D* for the twin tasks of statistical significance tests–rarely rejecting H0 erroneously and very probably alerting us to underlying discrepancies as large as δ4 –without calling it “relevant” in any way. Yet the very fact that Senn felt the need to write a guest post in 2025 on this topic suggests (to me, anyway) that new terminology to go with his viewpoint would be useful. Now to let’s turn to topic (2) of this post:

Topic (2). How “redefine significance” (and Bayes factor ‘reforms’) promote the faulty construal that Senn is at pains to call out.

Start with what I call Senn’s ludicrous test:

“But where we are unsure whether a drug works or not, it would be ludicrous to maintain that it cannot have an effect which, while greater than nothing, is less than the clinically relevant difference” (Senn 2007, 201).

The main reason I said “we’re not done yet” in taking up Senn’s post is not terminology, but rather that what Senn warns against is fueled by what some statistical reformers promote.

I’m referring to a popular movement that hinges on the (mistaken) supposition that a statistically significant result ought to provide strong evidence for an effect associated with high power, i.e., δ4–according to the wishes of the statistical significance tester! This is the “redefine significance” movement, many of whose followers recommend replacing significance tests with Bayes factor (BF) tests. Senn has been sounding the alarm on that movement for some time; we should be listening.

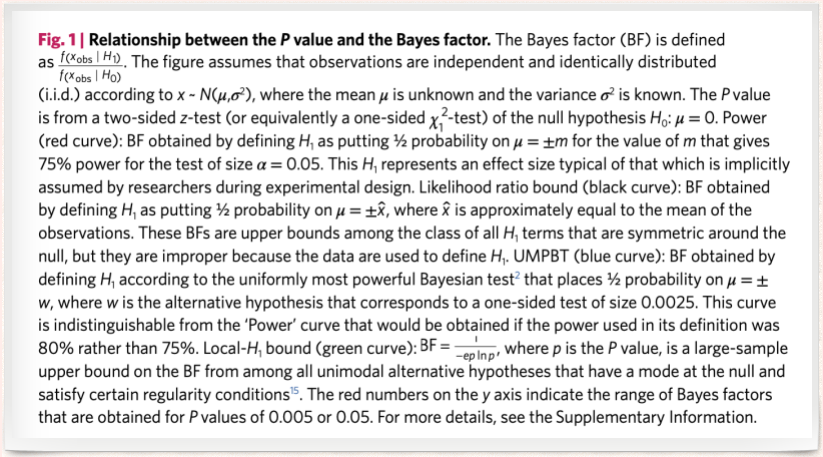

The BF redefiners provide ways to specify an “implicit alternative” the one thought to be implicitly used by statistical significance testers. The authors of (Benjamin et al. 2017) consider Bayes factors comparing a 0 point null to “classes of plausible alternatives”, where a plausible alternative is set at the value associated with high power, .75 or .8. (A few different approaches are given.) As they see it, “This H1 represents an effect size typical of that which is implicitly assumed by researchers during experimental design”. In their view, this is the effect size that statistical significance testers assume holds if H0 is false and H1 true. July 26 addition: See the description in Benjamin et al. 2017 at the end of this post.

From the Bayes factor perspective, the reason for setting high power to detect δ4, is to ensure the statistically significant result—just the point—is sufficiently probable assuming δ4, as compared to its probability under the null H0, set at 0.[2] They want this ratio to be around 15, 20, or 25 so that, with various priors assigned to the two hypotheses, H1 gets a high posterior (~.95). To this end, they recommend using a p-value threshold of .005. Whether that’s a good threshold is a separate question. The problem is that a BF test is very different from a statistical significance test. Significance testers are not testing 0 vs a difference against which a test has .8 power. They are not assuming that if there is a genuine effect it is highly clinically relevant δ4. As Senn says, this would be ludicrous. What error statistical researchers are doing is designing an experiment with a high enough probability of producing a statistically significant result D*, were the effect size as large as δ4—one that we would be (very) unhappy to miss.

What the redefiners think they’re doing, or purport to be doing, is aligning BF tests with statistical significance tests. They aver that this allows them to argue that what’s problematic for a BF tester is also problematic for a significance tester.[3]

From the perspective of the redefiners:

“A two-sided P-value of 0.05 corresponds to Bayes factors in favor of H that range from about 2.5 to 3.4 under reasonable assumptions about H. … This is weak evidence from at least three perspectives.”

None of the three is the perspective of the statistical significance tester.

“[W]e suspect many scientists would guess that P≈ 0.05 implies stronger support for H1 than a Bayes factor of 2.5 to 3.4. … [With a] prior odds of 1:10, a P value of 0.05 corresponds to at least 3:1 odds (that is, the reciprocal of the product 1/10 × 3.4) in favour of the null hypothesis!”

Perhaps ‘we (Bayes factor testers) would suspect that.’ But we (statistical significance testers) would suspect many scientists would guess that a good statistical account would not find evidence in favor of the null hypothesis of 0 when the lower bound of a .95 or .975 confidence interval exceeds 0 (and so excludes 0). We suspect they’d be very unhappy with an account that converted a method (such as statistical significance tests) that enables flagging various interesting discrepancies into a (ludicrous) test between no discrepancy and a highly clinically relevant one.[4] At the same time, the test has a low power to detect various population effects that might be of interest between 0 and δ4.[5] As Senn reminds us, “a nonsignificant result will often mean the end of the road for a treatment. It will be lost forever. However, a treatment which shows a ‘significant’ effect will be studied further” (Senn 2007, 202).

So, listen to Senn–statistical significance testers should be careful what they wish for– but they should also be careful to question when other approaches, with very different aims, dictate what they really wish for. That would be ludicrous.

Please share your thoughts and questions in the comments.

Notes

[1] The 4 deltas (from an earlier guest post by Senn) were:

1.It is the difference we would like to observe

2. It is the difference we would like to ‘prove’ obtains

3. It is the difference we believe obtains

4. It is the difference you would not like to miss.

[2] Their example involves testing the mean of a normal distribution rather than testing the difference of means, but the point is analogous.

[3] See Richard Morey for a critical discussion of the statistical arguments behind redefine statistical significance.

[4] Of course there’s a big difference in what’s being inferred. The BF tester is comparing point values of the parameter; whereas the significance test is not comparative, and infers that the parameter value exceeds some value, or is less than some value. I say “of course”, but have any BF testers stopped to discuss this? I ask readers to place examples in the comments.

[5] Note too that, even if the statistically significant result just reached the .005 level, the error statistician would not infer evidence of so large a population discrepancy as large as δ4 The p-value associated with testing that ∆ = δ4 would be ~0.5! Ironically, from the perspective of the significance tester, the BF construal is exaggerating the evidence warranted by a just statistically significant result. Moreover, the error probability control of statistical significance tests is lost, since BFs are insensitive to gambits that alter error probabilities—at least as standardly formulated.

Thanks, Deborah. I think I am nearly in complete agreement. I apologise if my original description of the issues was less than clear. In my defence, I can claim that the phrase clinically relevant difference can mean many different things and I can’t claim to own the definition. I would put it like this. If someone comes to me and says, for example, we need to design a trial in asthma with 80% power for a type I error rate of 5% and the clinically relevant difference is 200ml of forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), they need to understand that this implies that we are planning to use clinically relevant difference to mean a difference we should not like to miss. Having done so, we should be very careful in discussing any findings and we should be aware that others may use clinically relevant difference to mean something quite different.

I am not sure about the motives of those who have promoted the .005 standard. I seem to recall that at least one of the papers doing this suggested that the reason was to deal with “the replication crisis” and then suggested that a replication study could use the more conventional 0.05 standard to confirm a 0.005 finding. This would be necessary to allow the replication probability to be high enough to deal with the perceived replication problem. I myself don’t like to think of replication in these terms.

I also think that a lot of the Bayesian criticism depends on the assumption that point null hypotheses have an appreciable prior probability. In my field, drug development, this might be occasionally reasonable. An example might be the comparison of two optical isomers. (Caution! I am not a pharmacologist!) I understand that there might be some circumstances where the isomerism might be irrelevant to efficacy but one might wish to know if this were so. The famous Cushny and Peebles experiment is an example. Cushny and Peebles, optical isomers and the birth of modern statistics

However, there are others where it would be very odd. I have helped design three-armed trials in which a new treatment was compared to a standard with proven efficacy and a placebo. Clearly one cannot simultaneously believe that the new treatment has half a chance of being identical in effect to the standard and half chance of being identical to placebo, which are mutually exclusive, unless one believes it has no chance of being superior to standard, which would vitiate the point of the experiment. More generally that two different active treatments would be equipotent would be a remarkable coincidence.

Stephen:

Thank you for your reply.

It is true that these Bayesians generally give high priors to the null of no effect, but the same point is made when they consider “equipoise” assignments to the null and alternative. They consider Bayes factors comparing a 0 point null to “classes of plausible alternatives”, where a plausible alternative is set at the value associated with high power, .75 or .8. As they see it, “This H1 represents an effect size typical of that which is implicitly assumed by researchers during experimental design”.

As Benjamin et al., 2017 remark: “We propose 0.005 for two reasons. First, a two-sided P value of 0.005 corresponds to Bayes factors between approximately 14 and 26 in favour of H1. This range represents ‘substantial’ to ‘strong’ evidence according to conventional Bayes factor classification.” (The second reason is the alleged improved replication.) Val Johnson aligns the BF and the statistical significance test so that they both use the same rejection region (uniformly most powerful Bayesian tests), at least for cases he considers. The criticism about “weak evidence” then grows out of the fact that the two-sided .05 cut-off does not yield a high enough BF in favor of an H1, understood as the alternative associated with high power. But by using .005, as Val Johnson shows, the BF tester can take a just significant result as strong evidence for H1. For a test of a normal mean (1-sided), for instance, this gives a posterior for H1 of around .97. (See also note (5) of my blogpost.) I’m not saying this is a bad threshold in its own right, I’m simply pointing out that the redefine movement encourages the view that a statistically significant result ought to (or is intended to) provide evidence for an alternative associated with high power–the view that your guest post rightly criticizes. I’m sorry I don’t have time at the moment to spell this out more carefully. Please see pp 262-264 of SIST using this link https://errorstatistics.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/sist-excursion-4-tour-i.pdf

What I meant to add to the above comment was that a point where we might disagree is in the statement as to what Bayes factor proponents are doing. Maybe I misunderstand you but you wrote:

“We suspect they’d be very unhappy with an account that converted a method (such as statistical significance tests) that enables flagging various interesting discrepancies into a (ludicrous) test between no discrepancy and a highly clinically relevant one.”

However, I think that what the BF achieves is a comparison between a point null and any other non-null value.

The movement to which I’m alluding consists of BF testers. They do not merely report the comparative measures, but the outputs of tests. The test outputs are usually in terms of things like very strong, strong, weak etc. evidence for one of two hypotheses. Others would report a posterior probability based on this BF (some times with equipoise priors). The hypotheses, as described in Benjamin et al., 2017 consist of a null, 0 effect, and an alternative, a delta-4–a discrepancy we would not like to miss. My blogpost only concerns that very popular movement, and my point is that they make the supposition (about statistical significance testers) that you are on about. One of the 4 or 5 approaches (I have just now pasted the description under the figure given in Benjamin et al. 2017) is Val Johnson’s “uniformly most powerful Bayesian tests”. Significance testers and redefiners currently talk past eachother.

Thanks, for the clarification Deborah. We agree that the Bayesian camp seems to be split on this. It my commentary on the P-value/Significance ASA working party statement, that the ASA buried somewhere I tried to plot the commentaries in a two-dimenisonal space with dimensions pro/con Bayes and pro/con significance testing. The correlation was rather weak,