The mayor of NYC offered $30 an hour to help shovel the ~ 30 inches of snow that fell last Sunday and Monday. From what I hear, it was a very effective program. Here’s a little power puzzle to very easily shovel through [1]

The mayor of NYC offered $30 an hour to help shovel the ~ 30 inches of snow that fell last Sunday and Monday. From what I hear, it was a very effective program. Here’s a little power puzzle to very easily shovel through [1]

Suppose you are reading about a result x that is just statistically significant at level α (i.e., P-value = α) in a one-sided test T+ of the mean of a Normal distribution with n iid samples, and (for simplicity) known σ: H0: µ ≤ 0 against H1: µ > 0. I have heard some people say:

A. If the test’s power to detect alternative µ’ is very low, then the just statistically significant x is poor evidence of a discrepancy (from the null) corresponding to µ’. (i.e., there’s poor evidence that µ > µ’ ). I am keeping symbols as simple as possible. *See point on language in notes.

They will generally also hold that if POW(µ’) is reasonably high (at least .5), then the inference to µ > µ’ is warranted, or at least not problematic.

I have heard other people say:

B. If the test’s power to detect alternative µ’ is very low, then the just statistically significant x is good evidence of a discrepancy (from the null) corresponding to µ’ (i.e., there’s good evidence that µ > µ’).

They will generally also hold that if POW(µ’) is reasonably high (at least .5), then the inference to µ > µ’ is unwarranted.

Which is correct, from the perspective of the (error statistical) philosophy, within which power and associated tests are defined?

(Note the qualification that would arise if you were only told the result was statistically significant at some level less than or equal to α rather than, as I intend, that it is just significant at level α, discussed in a comment due to Michael Lew here [0])

Allow the test assumptions are adequately met (though usually, this is what’s behind the problem). I have often said on this blog, and I repeat, the most misunderstood and abused (or unused) concept from frequentist statistics is that of a test’s power to reject the null hypothesis under the assumption alternative µ’ is true: POW(µ’). I deliberately write it in this correct manner because it is faulty to speak of the power of a test without specifying against what alternative it’s to be computed. It will also get you into trouble if you define power as in the first premise of this post:the probability of correctly rejecting the null–which is both ambiguous and fails to specify the all important conjectured alternative. That you compute power for several alternatives is not the slightest bit problematic; it’s what you want to do in order to assess the test’s capability to detect discrepancies. There’s a power function. If you knew the true parameter value, why would you be running an inquiry to make statistical inferences about it?

It must be kept in mind that inferences are going to be in the form of µ > µ’ =µ0 + δ, or µ < µ’ =µ0 + δ or the like. They are not to point values! (Not even to the point µ =M0.) Most simply, you may consider that the inference is in terms of the one-sided lower confidence bound (for various confidence levels)–the dual for test T+.

POWER: POW(T+,µ’) = POW(Test T+ rejects H0;µ’) = Pr(M > M*; µ’), where M is the sample mean and M* is the cut-off for rejection at level α . (Since it’s continuous it doesn’t matter if we write > or ≥). I’m simplifying notation. Also, I’ll leave off the T+ and write POW(µ’).

In terms of P-values: POW(µ’) = Pr(P < p*; µ’) where P < p* corresponds to rejecting the null hypothesis at the given level.

Let σ = 10, n = 100, so (σ/ √n) = 1. Test T+ rejects H0 at the .025 level if M > 1.96(1). For simplicity, let the cut-off, M*, be 2.

Test T+ rejects H0 at ~ .025 level if M > 2.

CASE 1: We need a µ’ such that POW(µ’) = low. The power against alternatives between the null and the cut-off M* will range from α to .5. Consider the power against the null:

1. POW(µ = 0) = α = .025.

Since the the probability of M > 2, under the assumption that µ = 0, is low, the just significant result indicates µ > 0. That is, since power against µ = 0 is low, the statistically significant result is a good indication that µ > 0.

Equivalently, 0 is the lower bound of a .975 confidence interval.

2. For a second example of low power that does not use the null: We get power of .04 if µ’ = M* – 1.75 (σ/ √n) unit –which in this case is (2 – 1.75) .25. That is, POW(.25) =.04.[ii]

Equivalently, µ >.25 is the lower confidence interval (CI) at level .96 (this is the CI that is dual to the test T+.)

CASE 2: We need a µ’ such that POW(µ’) = high. POW(M* + 1(σ/ √n)) = .84.

3. That is, adding one (σ/ √n) unit to the cut-off M* takes us to an alternative against which the test has power = .84. So POW(T+, µ = 3) = .84.

Should we say that the significant result is a good indication that µ > 3? No, there’s a high probability (.84) you’d have gotten a larger difference than you did, were µ > 3.

Pr(M > 2; µ = 3 ) = Pr(Z > -1) = .84. It would be terrible evidence for µ > 3!

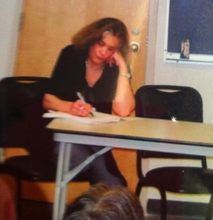

Blue curve is the null, red curve is one possible conjectured alternative: µ = 3. Green area is power, little turquoise area is α.

Note that the evidence our result affords µ > µ’ gets worse and worse as we drag µ further and further to the right, even though in so doing we’re increasing the power.

As Stephen Senn points out (in my favorite of his guest posts), the alternative against which we set high power is the discrepancy from the null that “we should not like to miss”, delta Δ. Δ is not the discrepancy we may infer from a significant result (in a test where POW(Δ) = .84), nor one that we believe obtains.

So the correct answer is B.

Does A hold true if we happen to know (based on previous severe tests) that µ <µ’?

No, but it does allow some legitimate ways to mount complaints based on a significant result from a test with low power to detect a known discrepancy.

It does mean that if M* (the cut-off for a result just statistically significant at level α) is used as an estimate of µ, with no standard error given, although we know independently that µ < M*, then M* is larger than µ. This is a tautology, and crucial information about the unreliability of the estimate is hidden. While it might be said that your observed result, which we’re assuming is M*, “exaggerates” µ, if you were to use it as an estimate, without reporting the SE, it is more correctly describing a misuse of tests, which would direct you to use the lower limit of a confidence interval if you were keen to estimate effect size once finding significance. Why is it highly unkosher for a significance tester? Despite knowing µ < M* (one of the givens of the example), it’s estimated as M*–as if there’s no uncertainty.

If the study is in a field known to have lots of researcher flexibility, it might legitimately raise the question of whether the researchers cheated, reporting only the one impressive result after trying and trying again, or tampered with the discretionary points of the study to achieve nominal significance. This is a different issue, and doesn’t change my answer. More generally, it’s because the answer is B that the only way to raise the criticism legitimately is to challenge the assumptions of the test.

Why does the criticism arise illegitimately? There are a few reasons. In some circles it’s a direct result of trying to do a Bayesian computation and setting about to compute Pr(µ = µ’|Mo = M*) using POW(µ’)/α as a kind of likelihood ratio in favor of µ’. Notice that supposing the probability of a type I error goes down as power increases is at odds with the trade-off that we know holds between these error rates. So this immediately indicates a different use of terms.

[1] This is a modified reblog of an earlier post.

*Point on language: “to detect alternative µ'” means, “produce a statistically significant result when µ = µ’.” It does not mean we infer µ’. Nor do we know the underlying µ’ after we see the data, obviously. The power of the test to detect µ’ just refers to the probability the test would produce a result that rings the significance alarm, if the data were generated from a world or experiment where µ = µ’.