.

Have the points in Stephen Senn’s guest post fully come across? Responding to comments from diverse directions has given Senn a lot of work, for which I’m very grateful. But I say we should not leave off the topic just yet. I don’t think the core of Senn’s argument has gotten the attention it deserves. So, we’re not done yet.[0]

I will write my commentary in two parts, so please return for Part II. In Part I, I’ll attempt to give an overarching version of Senn’s warning (“Be careful what you wish for”) and his main recommendation. He will tell me if he disagrees. All quotes are from his post. In Senn’s opening paragraph:

…Even if a hypothesis is rejected and the effect is assumed genuine, it does not mean it is important…many a distinguished commentator on clinical trials has confused the difference you would be happy to find with the difference you would not like to miss. The former is smaller than the latter. For reasons I have explained in this blog [reblogged here], you should use the latter for determining the sample size as part of a conventional power calculation.

To avoid confusion, I use ∆ for the parametric (or population) differences–which I call discrepancies–and D for the observed differences, in this case, differences in means in a clinical trial.

Senn’s “difference you would be happy to find” concerns an observed difference D. His “difference you would not like to miss” concerns a parametric discrepancy ∆. Senn uses δ4 to represent the value of the clinically relevant parametric discrepancy ∆.

Power. I often say on this blog that power is the most misunderstood concept in error statistics. It still is (unfortunately). As I see it, the power of a test measures the test’s capability of informing us of the existence of an underlying parametric discrepancy ∆’ (or parametric effect size). We don’t see the underlying discrepancy or population effect size, but we are informed when an observed test statistic D reaches statistical significance at a chosen level. Power is a subjunctive conditional answering the question: what’s the probability this test would result in a statistically significant D, were it to have been generated by ∆’?[1]

POW(∆ = ∆’) = Pr(test yields a statistically significant D; under the assumption it was generated by ∆ = ∆’)

Let D = 2SE be the cut-off for a just statistically significant D. Call it D*.

POW(∆ = ∆’) = Pr(D > D*; ∆ = ∆’) [1-sided positive]

“Suppose, ..that we should like to have 80% power, … for the case when the ‘true’ value of the treatment effect is exactly equal to δ4.”

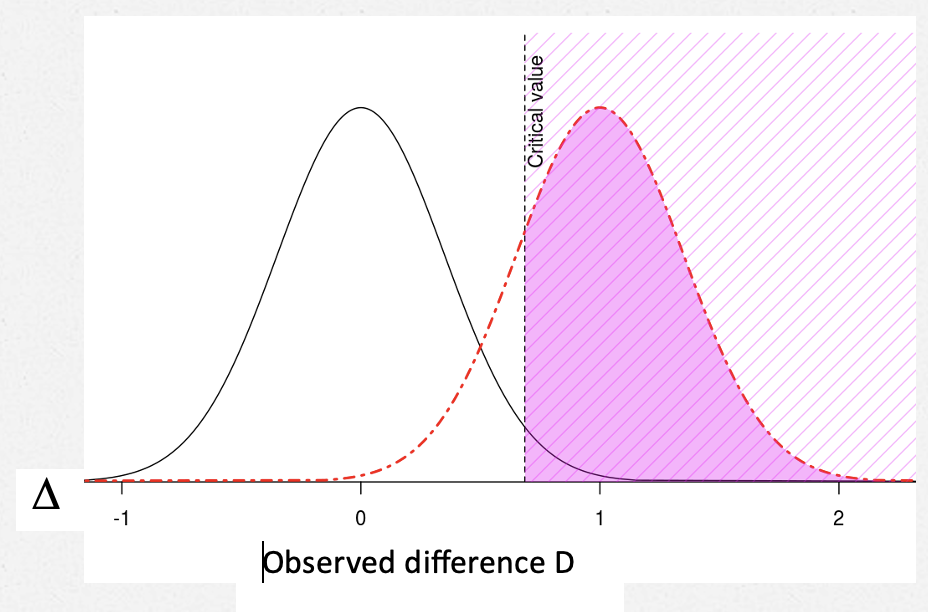

Adding .85 SE to the 2SE cut-off for statistical significance gets us to a value of ∆ against which the test has .8 power. That is, it gets us to δ4 . Since Senn sets δ4 to 1, we have SE = 1/2.8 = 0.35.

The POWER against (∆ = δ4) = .8

The critical value of D, D*, is 2SE = .7 (I’m using 2SE rather than 1.96 SE.) [2]

So an observed result that is just statistically significant–one that just makes it to D*–is not clinically significant. It is “only” .7, whereas, clinical significance is set at 1.

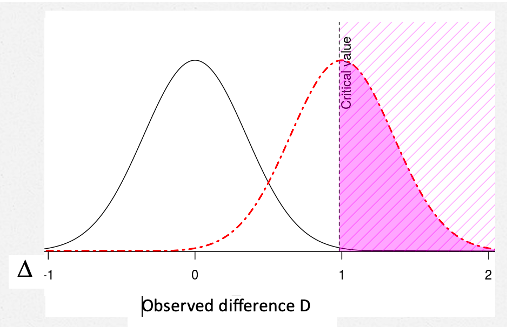

Suppose, to get your wish, you make D* bigger, say = δ4? Here’s Senn: “However, if we take the value of δ4 = 1 used for planning the trial as defining clinical relevance and we add the further requirement for success that [D*] should also be equal to δ4, then …using this (unwise) standard” the power to detect δ4 “will not be 80% as planned but only 50%”.

The POWER against (∆ = δ4) = .5

With this new, higher hurdle for D*, the power to detect ∆ = 1 is .5. [3] Note too that the p-value corresponding to this new D* will not be .025 (one-sided) or .05 (two-sided), but much smaller, around .003 (or .006).[4]

How much worse do things get “if we make the further requirement that not only should we observe a clinically relevant difference [when D just reaches statistical significance]”, but we should also have evidence that ∆ > 1 “for example by obtaining a confidence interval that excludes any inferior values”. [5]

What is the solution? “The only possible solution is to use a definition of clinical relevance for judging practically the acceptability of a trial result that is more modest than that used for the power calculation”: If we set δ1 = 0.7. “we have the consequence that a significant result (D ≥ D*) is a clinically relevant one“.

Note, of course, as discussed above, this is a standard for observing a clinically relevant difference. It would be naïve to assume that, just because we have (a) ‘rejected’ a null hypothesis and (b) observed a clinically relevant difference, we can therefore conclude that the difference is necessarily that observed.

Upshot. By defining a clinically relevant observed D “for judging practically the acceptability of a trial result” equal to D* (in this case, if we set δ1 = 0.7), our test is highly capable of yielding statistical significance D* when the underlying parametric discrepancy ∆ is one we would be very unhappy to miss. The power to detect ∆ = 1 is .8. You can also get your wish of being happy to find a D that is just statistically significant.

This, I take it is the gist of Senn’s guest blogpost. Does Senn agree? In Part II, I will recommend a terminological modification, but aside from that I concur with Senn. I will also be drawing out a main consequence and making one or two further points–so please return to check it out.

I invite readers to share thoughts and queries in the comments.

[0] This is the picture I used when I started blogging.

[1] Power to detect ∆’ goes in the opposite direction as the severity associated with ∆ > ∆’. However, if a test has high power to detect ∆’, then a nonsignificant result indicates ∆ < ∆’. If power is to be used to ascertain discrepancies well or poorly warranted post data, I recommend using “attained power”. Search power howlers, and power on this blog.

[2] Senn also identifies D* with δ1 , but I try to keep all deltas for the parametric discrepancy.

[3] A good example of confusing “higher hurdle” with “higher power” is illustrated by Ziliac and McCloskey. Higher hurder leads to lower power. See this post from 2014 “to raise the power of a test is to lower (not raise) the ‘hurdle’ for rejecting the null”.

[4] I agree with Cox (2006, 35) that, with few exceptions, the two-sided test should be seen as two one-sided tests, with a correction for selection. (Principles of Statistical Inference).

[5] Senn speaks of being able to “prove” ∆ > 1, but I think that’s too strong; he may have meant “show”.

Thanks, Deborah. I agree with your interpretation and elaboration of what I wrote. I think, however, as regards your footnote [5] I did mean “prove” but only in the conventional sense of “rejecting” the shifted null using a significance test . I regard the wish to do this as being (usually) hopelessly impractical. It was discussed in my delta force post of some years ago, where I looked at the four possible views of statistical relevance and stated

“It is the difference we would like to ‘prove’ obtainsThis view is hopeless. It requires that the lower confidence interval should be greater than δ. If this is what is needed, the power calculation is completely irrelevant.”

Stephen:

Thank you so much for your reply, I’ve been slow in getting around to Part II, and I am very glad to have your reply first, and happy you agree with my rough summary. The terminology issue, or possible one, is this: I traced your remarks and terminology, much of it is in bold in this blogpost. What happens, in following your suggestion, it seems to me is that we ends up saying both:

“for judging practically the acceptability of a (statistically significant) trial result”.

Do you agree that this would be confusing (or not)? You would be the one to choose a proper modified term. Could (B) be “D* is a practically relevant observed difference?” Or, maybe delta 4 (in this example, set to 1) could be called “the highly clinically relevant (population) discrepancy”. Then D* (the critical value for D) could be the (merely) clinically relevant (observed) difference.

I get your point about my footnote (5): My reason for preferring “show” or “provide evidence for”, rather than “prove”, is to avoid unnecessary skirmishes with the “retire statistical significance” crowd, e.g., Amrhein, Greenland and McShane (2019) who emphasize “Nor do statistically significant results ‘prove’ some other hypothesis”.

https://media.nature.com/original/magazine-assets/d41586-019-00857-9/d41586-019-00857-9.pdf

Thanks, Deborah. I start from the arrogant position that the only useful starting point for delta in a power calculation is that delta is the difference one would not like to miss. This is what I use. Confusion arises because others use definitions I don’t like.

I don’t really want to go down the “rabbit hole” of discussing further all the other deltas that people use. Once we have a confidence interval for the treatment effect then everyone is free to draw what conclusions they like from the data (including whatever other evidence they have). At this point I think that labels become irrelevant.

Stephen:

Perhaps I wasn’t clear (or I misunderstand something). I totally agree with your starting point that delta in a power calculation is the (parametric) difference one would not like to missI The trialist would be very unhappy if they were dealing with an underlying effect as large as delta-4, and yet a minimally significant difference, D*, did not emerge from the trial. That’s why the power is set fairly high for delta-4).

I thought your point was to acknowledge A (D* is less than delta-4), while recommending something new, namely B– D* be regarded as a clinically relevant observed difference, “for judging practically the acceptability of a (statistically significant) trial result”. This makes sense, the issue I raised was terminological. You use the term “clinically relevant in both A and B. I was suggesting that asserting both A. and B. could be confusing, and asking you about possibly modifying B. Maybe you don’t really want people to say B, and so I was mistaken. Maybe you just want them to recognize that it makes sense to view D* as (clinically?) relevant “for judging practically the acceptability of a (statistically significant) trial result”. (The solution should be applicable, of course, outside clinical trials.) Thank you for clarifying.

My view is that you should make a good job of planning a clinical trial and for that purpose, if you are going to use the conventional approach, you need a delta. I recommend thinking of delta as the difference you would not like to miss.

However, once the trial is in it is no longer important. As David Cox said in 1958 “Power is important in choosing between alternative methods of analysing data an in deciding on an appropriate size of experiment. It is quite irrelevant in the actual analysis of data.” [1] (p161)

Different people may disagree as to what delta should mean and what value it should have. Once the analysis is in, they can come to their own conclusions. We don’t need to agree on the labels. Whoever plans the trial has to decide on a delta but whatever value is chosen, others are not party to that decision.

Personally, as a statistician, I don’t care. I plan the trial I calculate the confidence interval. If others want to discuss some meaning beyond the numbers that are delivered, “that’s not my department”.

It may be that I am failing to see some deep point here but really all I was trying to illustrate in my blog was some various trivial consequences of statistical analysis and warning commentators on making requests that seem reasonable, “not only significance but also relevance,” without thinking it through.

[1]Cox, D. R. (1958). Planning of Experiments. New York, John Wiley.

Stephen:

I revised my previous comment a little to better explain my point which does not deal with power or its post-data relevance. It’s not a deep point, but one of the terminology. you wrote: “The only possible solution is to use a definition of clinical relevance for judging practically the acceptability of a trial result that is more modest than that used for the power calculation. If we set δ1 = 0.7 …we have the consequence that a significant result is a clinically relevant one.” This seems to say, with this recommendation, a significant result can be said to be a clinically relevant one (claim B). But, given A, I was suggesting, this could be confusing. The additional clause “for judging practically the acceptability of a trial” needs to be attached whenever one would say B. Maybe as a shorthand, it could be called the practically relevant observed difference, or the like.