.

John Park, MD

Medical Director of Radiation Oncology

North Kansas City Hospital

Clinical Assistant Professor

Univ. Of Missouri-Kansas City

[An earlier post by J. Park on this topic: Jan 17, 2022: John Park: Poisoned Priors: Will You Drink from This Well? (Guest Post)]

Abandoning P-values and Embracing Artificial Intelligence in Medicine

The move to abandon P-values that started 5 years ago was, as we say in medicine, merely a symptom of a deeper more sinister diagnosis. Within medicine, the diagnosis was a lack of statistical and philosophical knowledge. Specifically, this presented as an uncritical move towards Bayesianism away from frequentist methods, that went essentially unchallenged. The debate between frequentists and Bayesians, though longstanding, was little known inside oncology. Out of concern, I sought a collaboration with Prof. Mayo, which culminated into a lecture given at the 2021 American Society of Radiation Oncology meeting. The lecture included not only representatives from frequentist and Bayesian statistics, but another interesting guest that was flying under the radar in my field at that time… artificial intelligence (AI).

Fast forward 3 years from that meeting: AI and Machine Learning (ML) have taken medicine by storm with the rise of large language models being adapted to specific diseases, automated reading of images, and even contouring of cancers in radiation oncology. Given there was no firm statistical foundation, it is not surprising medicine has given way to AI/ML data analysis essentially without challenge once again.

The current state is like the wild, wild, west with academic medicine publishing AI/ML papers at an incredible rate in all the top oncology journals. The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) even created its own spin off journal called NEJM AI. Looking at these papers there is no uniform consensus on how to validate big data results. Severity is severely (pun intended) lacking. This is further compounded by the fact that traditional statistics, no matter what the flavor, were looking for causal inferences, however for AI methodologists, some say it is not their concern and many ML algorithms do not try to quantify error rates (Watson, Synthese, 2023). The usual concerns about normality, independence, and identical distributions do not apply because frequently there are no strong assumptions about the data. Along with the fact that many algorithms are black boxes with proprietary rights and even if we could see the algorithm, we could not understand it.

Further compounding the issue there are no universal algorithms being used, whereas, in most medical research regression models, Kaplan-Meier analysis, etc. are standardized. A snapshot of 3 articles from top oncology journals display the disparate methodologies used.

| Study | Algorithm | Training Methodologies |

| Bladder Cancer Lymph Node Detection (Wu, Lancet Oncol, 2023) | High-Resolution Net (HRNet) neural network using a novel architecture that ran multi-resolution streams in parallel | Dynamic balanced sampling scheme with hard negative mining approach, F2 Score, Brier Score, ROC Curve |

| Multiple Myeloma Prognostication (Maura, JCO, 2024) | 3 algorithm approach using multivariate cox-proportional-hazard with regularization, random survival forest, and neural networks | 5-fold cross validation (repeated x 10), Harrell’s and Uno’s Concordances, Integrated Brier Score, Negative Binomial Log-likelihood |

| Lung Cancer Toxicity Prediction (Ladbury, IJROBP, 2023) | 6 algorithm Interpretable ML approach using logistic regression, naive Bayes, k-nearest neighbors, support vector machine, random forest, and extreme gradient boosting | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) TomekLinks method, the SMOTE-Edited Nearest Neighbors method, tabular generative adversarial networks, 10-fold cross validation to maximize AUC, Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) framework |

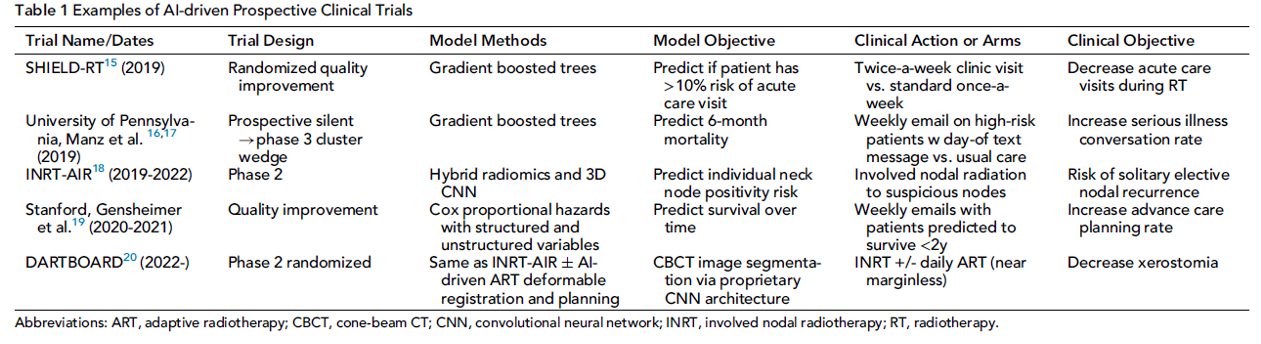

The question now is are we able to severely test AI/ML studies? First, we can subject the AI algorithms to prospective clinical trials and subject them to rigorous testing in this manner. The table below is list of trials from a paper my colleagues and I wrote discussing the integration of AI/ML into oncology trials (Kang, Sem Rad Onc, 2023).

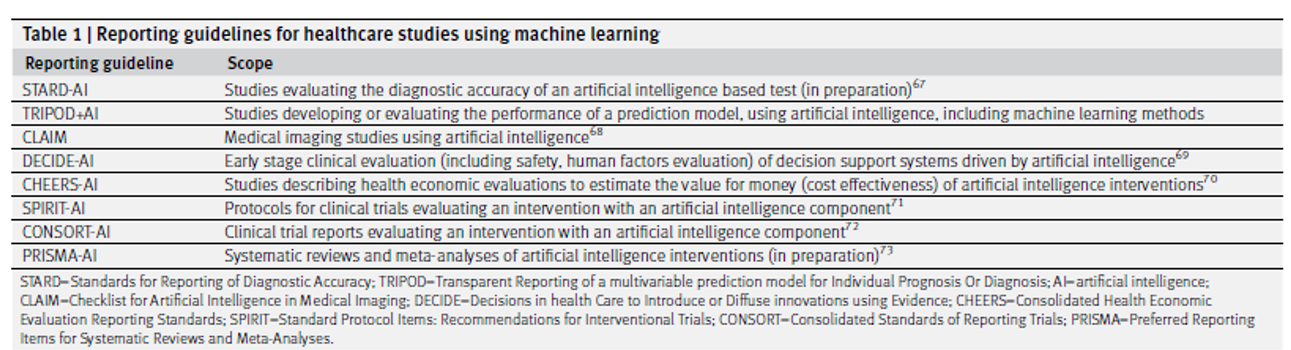

Although, in my humble opinion, this is the best way test the AI/ML methods, it will not be feasible to test the multitude of algorithms that way. A good start to this problem is the formation of AI/ML guidelines such as TRIPOD+AI that provide authors a checklist to “to promote the complete, accurate, and transparent reporting of studies that develop a prediction model or evaluate its performance” (Collins, BMJ, 2024). Given the multiple different types of data analysis, there are also different guidelines for when AI reads medical imaging vs analyzing data points per the table below (Collins, BMJ, 2024).

An area that needs much more growth is on what constitutes severe testing for AI/ML. The stakes are much higher for cancer patients than say for shopping preferences when looking at A/B testing. Trying to make the models more transparent with explainable AI (XAI), runs into the problems of ambiguous fidelity, lack of severe testing, and an emphasis on product over process (Watson, Synthese, 2023). The other question is when are AI/ML methods actually needed? In a study comparing statistical methods (Cox model and accelerated failure time model with log-logistic distribution) with ML methods (random survival forest and PC-Hazard deep neural network), the ML methods needed 2-3 times the sample size to achieve the same performance (Infante, Stats in Medicine, 2023), asking the question how many studies actually need the power of AI/ML, as opposed to being the hot topic that is publishable? I do not have any answers, save for prospectively testing these methods in clinical trials, but before the answers come these questions must be raised. The aforementioned guidelines are a start, but it is hard to see, or at least it is not explicit, how effective they are at safeguarding against bias, irreproducibility, or distinguishing signal from noise. These were the same warnings given out five years ago when P-values and statistical significance were called to be abandoned. My hope is that they will be heeded.

References

Infante, G., Miceli, R., Ambrogi, F. Sample size and predictive performance of machine learning methods with survival data: A simulation study. Statistics in Medicine. Volume 42, Issue 30, p5657-5675 (2023).

Kang, J., Chowdhry, A.K., Pugh, S.L., Park, J.H. Integrating Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Into Cancer Clinical Trials. Seminars in Radiation Oncology. Volume 33, Issue 4, p386-394 (2023).

Ladbury, C., Li, R., Danesharasteh, A., et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence to Identify Dosimetric Predictors of Toxicity in Patients with Locally Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of RTOG 0617. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics. Volume 117, Issue 5, p1287-1296 (2023).

Maura, F., Rajanna, A.R., Ziccheduu, B., et al. Genomic Classification and Individualized Prognosis in Multiple Myeloma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. Volume 42, Number 11 (2024).

Watson, D.S. Conceptual challenges for interpretable machine learning. Synthese. Volume 200, Article 65, (2022).

Wu. S., Guibin, H., Xu, A. et al. Artificial intelligence-based model for lymph node metastases detection on whole slide images in bladder cancer: a retrospective, multicentre, diagnostic study. Lancet Oncology Volume 24, Issue 4, p360-37, (2023).

I am very grateful to John Park for his guest post on the current “wild, wild west” he finds in current medical practice. It’s very illuminating to have a medical doctor’s input. He writes: “The move to abandon P-values that started 5 years ago was, as we say in medicine, merely a symptom of a deeper more sinister diagnosis.” I’d not heard of diseases being given sinister intensions. Interestingly, Park suggests that “within medicine, the diagnosis was a lack of statistical and philosophical knowledge…. Given there was no firm statistical foundation, it is not surprising medicine has given way to AI/ML data analysis essentially without challenge once again” (as with Bayesian methods). But does he really think that a firm statistical foundation would (or should) have blocked the onslaught of AI/ML in medicine? I don’t know, I’m just learning and am only a patient. Does he find a tension between what doctors would typically prescribe and what the machine tells them to do?

Park claims “the usual concerns about normality, independence, and identical distributions do not apply because frequently there are no strong assumptions about the data”. I find this very puzzling because my understanding is that IID data is an important assumption for ML algorithms to predict accurately, even within the universe of data used in the algorithm.

To really work, they may need an even stronger assumption–that the training data are representative (in some sense) of future data. What does Park think?

I’m intrigued with Park’s suggestion that “we can subject the AI algorithms to prospective clinical trials and subject them to rigorous testing in this manner”. I will encourage Park to write a follow-up to this post (or at least an extensive comment) after he returns from his much-deserved vacay in order to explain the specific claims that he and his colleagues are testing. And is the target of these tests the particular medical claim (e.g., about patient survival) or the algorithm leading to the claim. in the table he provides from (Kang, Sem Rad Onc, 2023)? Also, what are the results of these tests of AI/ML? Does the ML algorithm pass reasonably well? or not? How can I find out?

“The other question is when are AI/ML methods actually needed? In a study comparing statistical methods (Cox model and accelerated failure time model with log-logistic distribution) with ML methods (random survival forest and PC-Hazard deep neural network), the ML methods needed 2-3 times the sample size to achieve the same performance (Infante, Stats in Medicine, 2023), asking the question how many studies actually need the power of AI/ML, as opposed to being the hot topic that is publishable?”

“An area that needs much more growth is on what constitutes severe testing for AI/ML”. Indeed, and I have no doubt it’s doable. Please say some more about how the clinical trials of ML algorithms work, and whether they’re passing the test.

John Park’s testimonial is another evidence for the time collocation of AI/ML explosive appearance and the “statistics wars”. I am glad John refers to checklists. I guess medicine is well aware of their value. They offer both operational and pedagogical advantages. For a suggested lcheckist in applied statistics, that includes evaluating severe testing and probabitveness, see https://chemistry-europe.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ansa.202000159. See also https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4683252, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3591808, https://content.iospress.com/articles/statistical-journal-of-the-iaos/sji967

Ron:

I’m glad you read and commented on Park, as he seems to take a rather different stand than you. In your post you say that AI/ML has made the Fisherian goals obsolete, but he appears to describe how medicine is striving to bring them back, e.g., with testing AI/ML using RCT trials, which would be analyzed using p-values. Still I have many questions for him.

Mayo

I fully concur with John Park. He seems to agree that the AI/ML paradigm is changing the Fisherian perspective. My main point is that the modern statistical perspective needs to find how to get synergies from their combination.

What I did say is that in many industries, groups of statisticians have been somehow replaced by groups focused on AI/ML. This is different from how you perceived my message 🙂 It also mainly applies to non regulated industries, i.e. not in drug development and CMC or finance (risk management), although things are changing fast even there.

In fact, I brought up elsewhere that the current Chief Data Scientist’s job description should by an updated version of Deming’s Director of Statistical Methods. Many points in Deming’s recommendations still hold, but some face lifting is required. We elaborate on this in https://www.wiley.com/en-be/The+Real+Work+of+Data+Science%3A+Turning+data+into+information%2C+better+decisions%2C+and+stronger+organizations-p-9781119570707

Ron, I agree that the AI/ML paradigm is changing the Fisherian perspective, albeit not theoretically, but just practically, as traditional statistics is in some danger of being obsolete – at least it’s not the cool kid on the block so to speak (was it ever?). As I noted above, in medicine, this wasn’t really due to the elegance of the models and their predictive ability, but just their cultural force that has changed everything it has touched. Everyone must get used to the change, just like many physicians had a rough time with the change from paper to electronic medical records, statistics and as medical studies, will need to embrace AI/ML whether they want to or not. As Prof. Mayo noted above, this does not mean AI/ML should get a free pass, I am trying to see if there is a way to find a valid error probe / severe test for these algorithms. I believe that is the next frontier to be explored and at this point subjecting them to the rigors of randomized control trials (RCT) seem to be the only way for now, but this cannot be the only way due to budgetary and logistical constraints. Medicine I feel will be poorer off if the only way we can implement AI/ML is through the RCT apparatus.

Ron,

I am a fan of checklists and am influenced by the The Checklist Manifesto by Gawande and Noise by Kahneman (which I am sure you a familiar with). I really enjoyed the links you shared and may use something similar to that as I continue my work in AI/ML severe testing. If possible, could I receive a copy of the paper your paper “Helping authors and reviewers ask the right questions: The InfoQ framework for reviewing applied research.” It is behind a firewall.

Sure. Tried sending these to your va.gov email but the email bumped back. Where should I send them to?

Ron:

I had not heard the term “collocation” (actually, you say “time collocation”) used to express a coincidence in time. Collocation is said to be “the habitual juxtaposition of a particular word with another word or words with a frequency greater than chance”. (e.g., heavy drinker, statistical significance).

Anyway, the two were running in parallel for some time, and I don’t think there’s any genuine connection between the two–do you? I suppose there could be, but it seems slight. I recall early on in this blog, Larry Wasserman, who ran his own blog at that time, Normal Deviate, was heralding the coming of data science. There was a lot of hand-wringing about its usurping statistics. Well it all happened as some feared, and many departments changed their names and altered courses.Since high powered methods and big data made it easy to find impressive-looking effects by chance, it raised the consciousness of cherry-picking and data dredging. But I think that, by and large, the two movements are essentially unrelated. What do people think?

I’m intrigued, and very glad, to see you include assessing severity in a check-list. I had gotten the impression at first that you didn’t think it was relevant to the kind of things you cared about. You also do an excellent job summarizing key points about severity and error statistics. One thing: I generally regard probativism and performance to be under the error statistical umbrella, and thus in sync with severity, whereas probabilisms, at least insofar as they embrace the likelihood principle do not. I reallize people like Jim Berger give different meanings to “error probabilities” (in terms of posterior probabilities).

Actually, come to think of it, some Bayesians have adopted a Bayesian version of severity. (I say it doesn’t work. I can link to an archived draft of a paper of mine.)

Mayo

What you refer to as collocation is referred to as “phrases” of Association Rules with positive life in text analytics. My intent was more literal, as you indicated.

I think Statistics, like any profession needs to have on going strategic discussions to exchange ideas on its current position and where it is headed.

The Data Science appearance on the analytic stage was initially ignored by Statisticians. Tukey’s insight on data analysis and Breiman’s two cultures description opened the door to a serious consideration of it.

My talk in https://neaman.org.il/en/On-the-foundations-of-applied-statistics also mentions Huber excellent book on data analysis (slide 8) where he starts by a need for a “Prolegomena i the theory and practice of data analysis”, a la Kant.

Kant wrote a Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysics That Will Be Able to Present Itself as a Science (German: Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysik, die als Wissenschaft wird auftreten können) in 1783, two years after the first edition of his Critique of Pure Reason

So, Tukey, Breiman and Huber anticipated Data Science and the Statistics community had early warnings. I believe this might be have been an indirect trigger for the “p-value” introspective considerations significantly enhanced by Ioannides papers. This, in addition to the incredible success of AI/ML. So, yes, the fact that these occurred together (time collocation) might be related.

Severe testing, and testing in general as John Park writes is important. I think there is also a challenge in contributing new methods and new ideas that enhance the discovery and not only evaluate things retrospectively.

We need a Prolegomena with constructive components to help position Statistics in this new landscape of analytics. My blog was focused on that.

PS The iid assumptions are related to the data generation process. The first assumption here is that the analysis needs to consider it. Many AI/ML methods do not.

Mayo

In this video I introduce the last two chapters on my springer book on Modern Statistics. You might find it of interest https://user-images.githubusercontent.com/8720575/180794703-c6f05f40-eefd-4e1a-93f9-42cb78e6a6b4.mp4?fbclid=IwAR08kOITzOhBUIYZhyclkrh_p7Ad9q53rnrwUicOmiUBHsbd4TwJgzkHepo

For info on the book see https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-07566-7

Ron:

I don’t know why WordPress is holding your (and some other) comments up for moderation. the setting is that one is allowed to post comments, without moderation, after the first one is approved. I’m sorry for the stalling, I’ll look into it.

Thank you for this opportunity and I appreciate your patience for this response. I believe the lack of firm statistical foundations idealistically may have slightly stalled, but realistically is unlikely to hold back the force that is AI. Rather than relying on academic arguments and demonstrations of effectiveness, the impact of AI/ML outside medicine, as a cultural phenomenon, has led to its adoption in almost every field, including medicine. Who would dare to be a Luddite and oppose AI/ML?

I have already been approached by at least one AI product vendor for clinical adaptation and feel the pressure to adopt will only intensify as time goes on. With Bayesian statistics, I advocated for physicians to be ready to critically appraise Bayesian studies, now we also need to be prepared to critically assess these algorithms prior to implementing them into clinical practice.

In terms of model assumptions, perhaps I came across that NIID does not apply at all, but I think I just wanted to emphasize that these are not as big of concern in the AI/ML world. I am happy to be fact checked here, but these assumptions are not applicable for certain situations (e.g. time-series data or data with spatial correlations) and in practice are not nearly as important as in traditional statistical methods, where violations of these assumptions are a big deal, but in AI/ML do not seem appear to raise too much of a concern if the algorithm can make highly accurate predictions. With messy medical data, although IID may hold within one’s training, testing, and validation sets, if the algorithm can predict well in other institutions as well as continuously with the passage of time, does it really matter? My answer is no.

When I remarked about the need for AI/ML methods, this really was a critique against the publish or perish mentality.It seems much research is conducted for publication alone. In medicine / academia that often is enough to boost your career, however, in business, these algorithms undergo prospective severe testing in that, if they do not boost internet traffic or make money than those selling the AI/ML algorithms go bankrupt. In order to see if we can go straight from model validation to the clinic(a long term goal), perhaps as a short term goal, we need severe testing of these models to see, with our limited resource, which should go on to be tested in prospective clinical trials. I’m afraid prospective testing in randomized control trials is the only way forward at the current moment. In light of this I will summarize the results of the prospective trials from the “Table 1 Examples of AI-driven Prospective Clinical Trials.”

SHIELD-RT https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/JCO.20.01688: Single institution that study showed that Twice-weekly evaluation vs once weekly evaluations reduced rates of acute care during treatment from 22.3% to 12.3% (difference, −10.0%; 95% CI, −18.3 to −1.6; relative risk, 0.556; 95% CI, 0.332 to 0.924; P = .02). This would be promising to move onto larger studies.

UPenn Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomized Trial https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology/fullarticle/2771756: Serious illness conversations (SIC) were conducted among 1.3% in the control group and 4.6% in the intervention group, a significant difference (adjusted difference in percentage points, 3.3; 95% CI, 2.3-4.5; P < .001). Among 3552 high-risk patient encounters, SICs were conducted among 3.4% in the control group and 13.5% in the intervention group, a significant difference (adjusted difference in percentage points, 10.1; 95% CI, 6.9-13.8; P < .001). Interesting, what ML in combination with behavioral nudges made famous by Richard Thaler can do.

INRT-AIR https://aacrjournals.org/clincancerres/article-abstract/29/17/3284/728551/Efficacy-and-Quality-of-Life-Following-Involved?redirectedFrom=fulltext: Phase II study single institution study showing that “In this study, we leveraged radiologic criteria and artificial intelligence (AI) to focus radiotherapy only on certain visible nodes, entirely eliminating elective neck irradiation (ENI)” with no reported solitary elective nodal recurrence at 2 years. This is a very interesting trial that is very promising in reducing radiation treatment volumes, but would not start until bigger studies are performed.

Stanford Advanced Care Planning Study https://ascopubs.org/doi/10.1200/OP.22.00128: Non-randomzied trial that showed clinics that received weekly emails of patients predicted to have < 2 year survival to a control cohort of clinics without such emails and the intervention group had an ACP documentation rate of 35% compared to 3% in the control. Similar to the UPenn trial, I am not personally interested in what this trial was trying to accomplish, but that AI can give physicians weekly emails to help improve documentation is great. Hopefully, in the near future, the AI can do most the documentation for us (not sure how patients feel about that, but physicians would love it).

DARTBOARD Study https://www.redjournal.org/article/S0360-3016(23)07827-6/abstract: Phase II single institution study that also used the AI assisted nodal de-escalation based on the INRT-AIR.. This study used INRT, but also used adaptive radiation therapy, which means the radiation volumes were changed daily vs only when needed. The results were not impressive as only some mild skin reactions were saved with daily adaptive radiation therapy. It was a lot of work for very little benefit.

These are the start of promising efforts and would feel confident in some of these moving forward into larger randomized phase 3 studies, namely the SHIELD-RT trial and INRT-AIR. The DARTBOARD study could move forward, but would recommend waiting until AI/ML can change the volumes on its own and not with physician intervention. For now, I believe all algorithms must undergo the same rigorous testing as any new technology or drug, namely through clinical trials, as no other current test can adequately demonstrate their effectiveness in clinical practice. In the future, if severe tests are developed that allow AI/ML to bypass the cumbersome trial system, that would be ideal, but for now, that time has not yet come.

John:

Just to focus on the importance of model assumptions, I think they are crucial in AI/ML. Here’s the first one I happened across, but I’ll find more.

https://medium.com/@kapooramita/the-power-of-iid-data-in-machine-learning-and-deep-learning-models-49651afb7882

You mention time series, yes, but this still requires meeting assumptions. I will check with my colleague Aris Spanos who is an expert here. I think the techniques will fail without the assumptions about dependence and distribution. You say who cares if it does a good job predicting entirely new cases? But that’s exactly what we need to check.

Prof. Mayo,

I am happy to be corrected in this area as I am a learning more and more on AI/ML daily. This sentence from this paper (https://www.ijcai.org/Proceedings/07/Papers/121.pdf) seems to sum up the mood well “The machine learning community frequently ignores the non-i.i.d. nature of data, simply because we do not appreciate the benefits of modeling these correlations, and the ease with which this can be accomplished algorithmically.” This seems to be in line with what Ron wrote above as well. I would love to hear others thoughts on this as well.

John:

I think there is a confusion here. The article you cite begins: “Most methods for classifier design assume that the training samples are drawn independently and identically from an unknown data generating distribution, although this assumption is violated in several real life problems.” They go on to say that in certain problems, making careful use of known correlations that strictly violate iid can be beneficial.This clearly shows the crucial relevance of the assumptions, and goes against the idea that one can be cavalier about them or that the proper “mood” is to just ignore them. Are we agreed about this? In fact I’ve read the results that you link before. So don’t suppose AI/ML methods are statistical assumption-free. Beyond satisfying the statistical model assumptions, be they iid or with correlations or what have you, I wonder about distinct assumptions in applying the AI/ML models to brand new cases. I will ask Aris Spanos to comment.

It is rather interesting that their work appeals to p-values to check their models.

John:

I’ve studied the examples in your links. Thank you so much for sending them, as I did not really understand what was being tested with the mini-description, and now I do. There’s some kind of great irony in the use of tried and true statistical significance tests in critically evaluating AI/ML innovations. I wonder if the deniers of the value of p-values would ever admit this as evidence against their “abandon significance” stance, or their claims that it rarely makes sense to evaluate evidence using p-values. (there was a claim to this effect in the 2019 TAS paper Gelman was co-author on.

I’m still not clear though on your group’s role: is it to collect and summarize the assessments of AI/ML in your field of medicine? By the way, I read someplace that radiologists would be replaced by AI/ML in the near future, relieving them of having to assess images every 2 seconds, or something like that. This might be one of the more promising areas. What do you think?

Our group is trying assess AI/ML models based on oncology databases.Given the cost of clinical trials, I foresee having to choose between several algorithms, and my concern is how do we choose between the competing AI/ML methods. My choice is to choose the ones that have survived the most stringent error probes / severe testing. How we do this is unknown, but as you know, a question we are looking at. As far as radiologists go, my colleague’s guess was that the future radiologist may be a manager of AI reads instead doing all the read themselves. Even in my field of radiation oncology, I can see in 20 years computers being able to draw and plan radiation therapy.

John:

I remain confused about a couple of things: “Our group is trying assess AI/ML models based on oncology databases.Given the cost of clinical trials, I foresee having to choose between several algorithms, and my concern is how do we choose between the competing AI/ML methods.” Are you referring to the question of which algorithm to use in your field of medical practice? And so you’re looking at databases that report on clinical trials that test, or try to test, the algorithms in order that you can use the results in choosing between AI/ML methods in medical practice?

Given how many different methods you describe are used in solving a single problem e.g., avoiding acute care episodes by meeting twice weekly with patients the algorithm identifies as high risk–there would seem to be a question as to which one to credit (when it seems to work). Also, there would seem to be enormous latitude in the choice of what to study, and which results to report in published articles, of the sort you find. Are they as likely to report failures? It would be good if the choice of which to test, and in what setting, would come from outside. (Of course, they would have to be claims amenable to testing in a reasonable amount of time, etc.) I thought, at first, when you described your project, it was going to involve your group doing a kind of Cochrane study on which AI/ML models were advantageous (an extremely tall order for a single group to carry out) as opposed to reporting on which have been analyzed (by others) and had their reports published, and what they found.

I’m guessing someone’s doing meta-analyses on all this somewhere? Or that AI/ML methods are themselves being applied to the task of testing if AI/ML methods “worked” in a given setting. That doesn’t seem far-fetched.

Prof. Mayo,

Given we are in such an early phase in this arena, not much has been done at all. Fundamentally, we are trying to answer “of which algorithm to use in your field medical practice” and if they indeed have “worked.” We have not gone too far beyond that as the questions, algorhitims, and category (ie data analysis, imaging analysis, interactive chatbots/LLMs,e etc.) , as you noted have a lot of latitude. I am unaware of any meta-analysis studies nor are we attempting a Cochrane like study at the moment. We have just paired it down to database studies for now. Right now, we are trying to assemble a team of experts to even start broaching these important questions.

John – Metanalysis is conducted with fixed or random effect models. However, the studies involved have a time stamp not accounted for. Moreover, it is very likely that a specific study is affected by preceding ones. Somehow such time effect is never mentioned in metanalysis.

A similar effect is affecting the reliability of software systems. When a bug is fixed, one consider the occurrence of previous bugs. This is how software reliability models work.

Why is metanalysis blind to previous studies? Perhaps because of the focus on treatment effect and not on modelling.

Ron, you are absolutely correct. The time effect has often been discussed in the meta analysis of radiation to the internal mammary lymph nodes in breast cancer patients. The older studies used outdated radiation techniques and less effective chemotherapy, but this is not often factored for at all. I am unsure of why this is not modeled, perhaps because it may add further subjectivity and complexity?