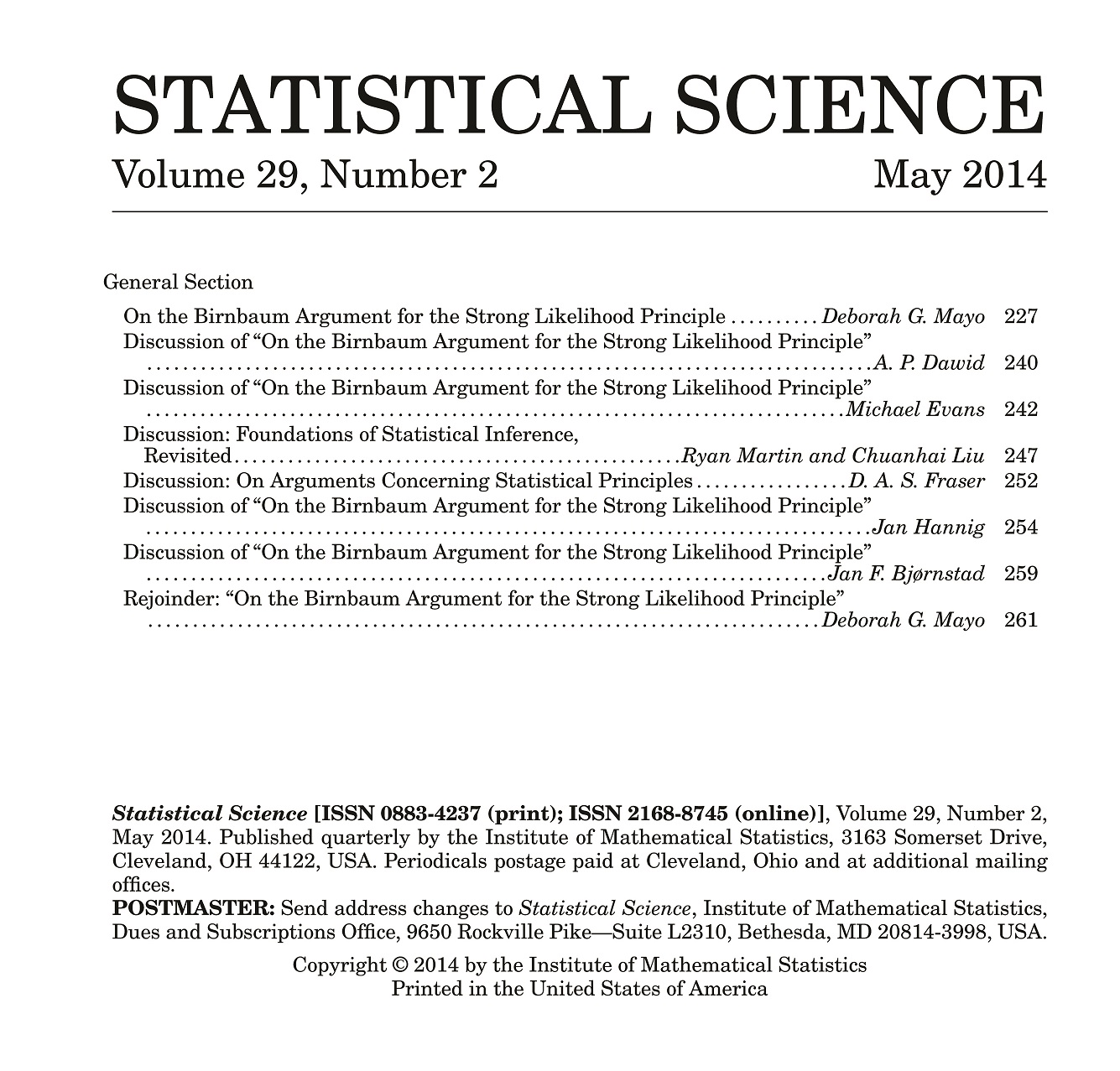

Abbreviated Table of Contents:

Abbreviated Table of Contents:

Here are some items for your Saturday-Sunday reading.

Here are some items for your Saturday-Sunday reading.

Link to complete discussion:

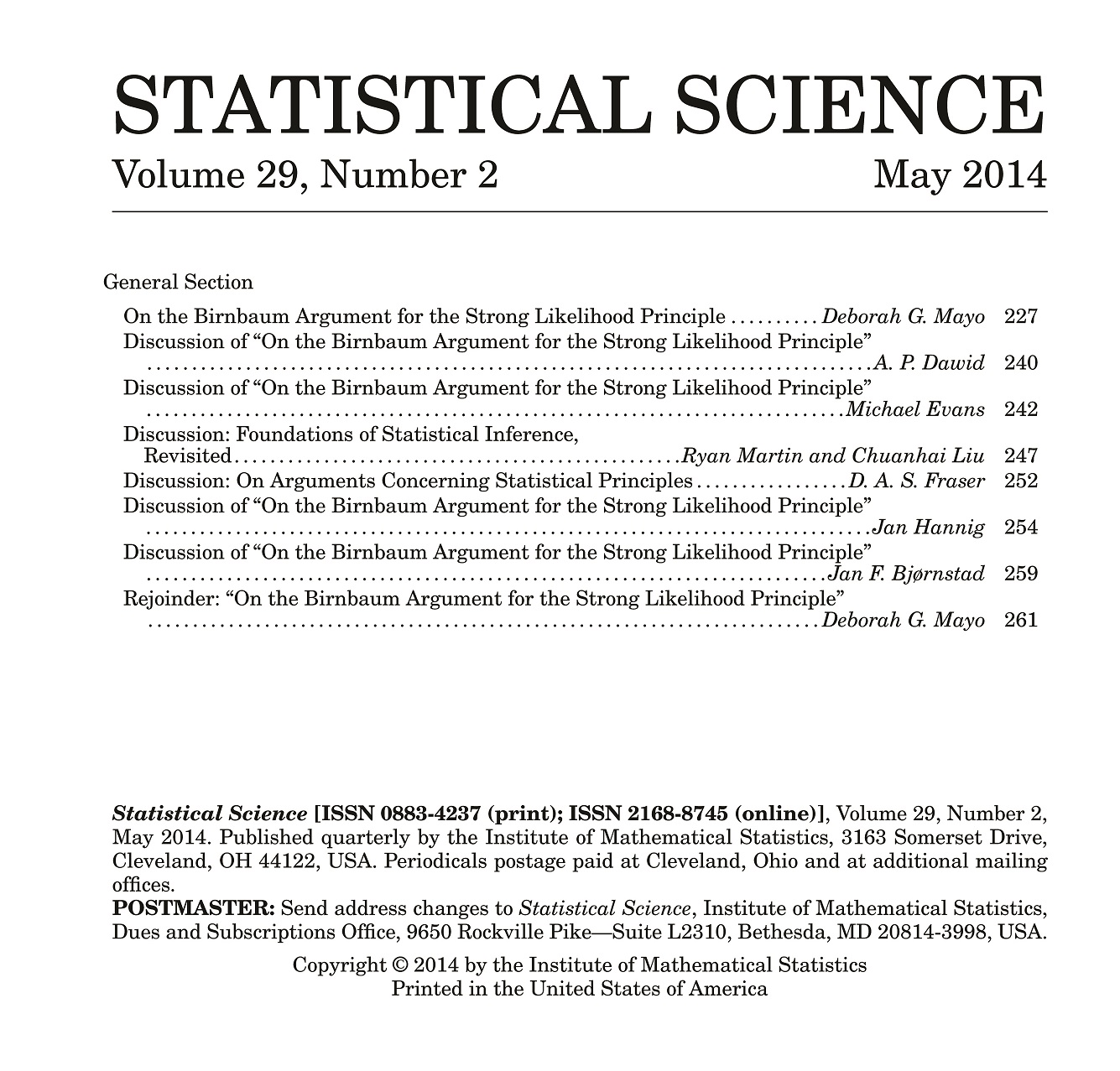

Mayo, Deborah G. On the Birnbaum Argument for the Strong Likelihood Principle (with discussion & rejoinder). Statistical Science 29 (2014), no. 2, 227-266.

Links to individual papers:

Mayo, Deborah G. On the Birnbaum Argument for the Strong Likelihood Principle. Statistical Science 29 (2014), no. 2, 227-239.

Dawid, A. P. Discussion of “On the Birnbaum Argument for the Strong Likelihood Principle”. Statistical Science 29 (2014), no. 2, 240-241.

Evans, Michael. Discussion of “On the Birnbaum Argument for the Strong Likelihood Principle”. Statistical Science 29 (2014), no. 2, 242-246.

Martin, Ryan; Liu, Chuanhai. Discussion: Foundations of Statistical Inference, Revisited. Statistical Science 29 (2014), no. 2, 247-251.

Fraser, D. A. S. Discussion: On Arguments Concerning Statistical Principles. Statistical Science 29 (2014), no. 2, 252-253.

Hannig, Jan. Discussion of “On the Birnbaum Argument for the Strong Likelihood Principle”. Statistical Science 29 (2014), no. 2, 254-258.

Bjørnstad, Jan F. Discussion of “On the Birnbaum Argument for the Strong Likelihood Principle”. Statistical Science 29 (2014), no. 2, 259-260.

Mayo, Deborah G. Rejoinder: “On the Birnbaum Argument for the Strong Likelihood Principle”. Statistical Science 29 (2014), no. 2, 261-266.

Abstract: An essential component of inference based on familiar frequentist notions, such as p-values, significance and confidence levels, is the relevant sampling distribution. This feature results in violations of a principle known as the strong likelihood principle (SLP), the focus of this paper. In particular, if outcomes x∗ and y∗ from experiments E1 and E2 (both with unknown parameter θ), have different probability models f1( . ), f2( . ), then even though f1(x∗; θ) = cf2(y∗; θ) for all θ, outcomes x∗ and y∗may have different implications for an inference about θ. Although such violations stem from considering outcomes other than the one observed, we argue, this does not require us to consider experiments other than the one performed to produce the data. David Cox [Ann. Math. Statist. 29 (1958) 357–372] proposes the Weak Conditionality Principle (WCP) to justify restricting the space of relevant repetitions. The WCP says that once it is known which Ei produced the measurement, the assessment should be in terms of the properties of Ei. The surprising upshot of Allan Birnbaum’s [J.Amer.Statist.Assoc.57(1962) 269–306] argument is that the SLP appears to follow from applying the WCP in the case of mixtures, and so uncontroversial a principle as sufficiency (SP). But this would preclude the use of sampling distributions. The goal of this article is to provide a new clarification and critique of Birnbaum’s argument. Although his argument purports that [(WCP and SP), entails SLP], we show how data may violate the SLP while holding both the WCP and SP. Such cases also refute [WCP entails SLP].

Key words: Birnbaumization, likelihood principle (weak and strong), sampling theory, sufficiency, weak conditionality

Regular readers of this blog know that the topic of the “Strong Likelihood Principle (SLP)” has come up quite frequently. Numerous informal discussions of earlier attempts to clarify where Birnbaum’s argument for the SLP goes wrong may be found on this blog. [SEE PARTIAL LIST BELOW.[i]] These mostly stem from my initial paper Mayo (2010) [ii]. I’m grateful for the feedback.

In the months since this paper has been accepted for publication, I’ve been asked, from time to time, to reflect informally on the overall journey: (1) Why was/is the Birnbaum argument so convincing for so long? (Are there points being overlooked, even now?) (2) What would Birnbaum have thought? (3) What is the likely upshot for the future of statistical foundations (if any)?

I’ll try to share some responses over the next week. (Naturally, additional questions are welcome.)

[i] A quick take on the argument may be found in the appendix to: “A Statistical Scientist Meets a Philosopher of Science: A conversation between David Cox and Deborah Mayo (as recorded, June 2011)”

UPhils and responses