.

Picking up where I left off in a 2023 post, I will (finally!) return to Gardiner and Zaharos’s discussion of sensitivity in epistemology and its connection to my notion of severity. But before turning to Parts II (and III), I’d better reblog Part I. Here it is:

I’ve been reading an illuminating paper by Georgi Gardiner and Brian Zaharatos (Gardiner and Zaharatos, 2022; hereafter, G & Z), “The safe, the sensitive and the severely tested,” that forges links between contemporary epistemology and my severe testing account. It’s part of a collection published in Synthese on “Recent issues in Philosophy of Statistics”. Gardiner and Zaharatos were among the 15 faculty who attended the 2019 summer seminar in philstat that I ran (with Aris Spanos). The authors courageously jump over some high hurdles separating the two projects (whether a palisade or a ha ha–see G & Z) and manage to bring them into close connection. The traditional epistemologist is largely focused on an analytic task of defining what is meant by knowledge (generally restricted to low-level perceptual claims, or claims about single events) whereas the severe tester is keen to articulate when scientific hypotheses are well or poorly warranted by data. Still, while severity grows out of statistical testing, I intend for the account to hold for any case of error-prone inference. So it should stand up to the examples with which one meets in the jungles of epistemology. For all of the examples I’ve seen so far, it does. I will admit, the epistemologists have storehouses of thorny examples, many of which I’ll come back to. This will be part 1 of two, possible even three, posts on the topic; revisions to this part will be indicated with ii, iii, etc., and no I haven’t used the chatbot or anything in writing this. Continue reading

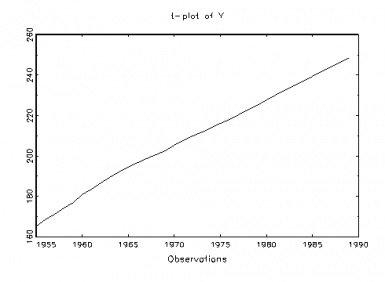

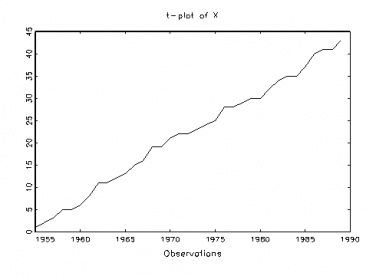

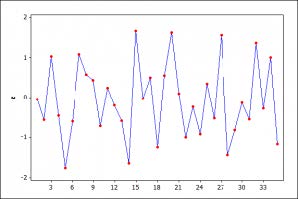

The Nature of the Inferences From Graphical Techniques: What is the status of the learning from graphs? In this view, the graphs afford good ideas about the kinds of violations for which it would be useful to probe, much as looking at a forensic clue (e.g., footprint, tire track) helps to narrow down the search for a given suspect, a fault-tree, for a given cause. The same discernment can be achieved with a formal analysis (with parametric and nonparametric tests), perhaps more discriminating than can be accomplished by even the most trained eye, but the reasoning and the justification are much the same. (The capabilities of these techniques may be checked by simulating data deliberately generated to violate or obey the various assumptions.)

The Nature of the Inferences From Graphical Techniques: What is the status of the learning from graphs? In this view, the graphs afford good ideas about the kinds of violations for which it would be useful to probe, much as looking at a forensic clue (e.g., footprint, tire track) helps to narrow down the search for a given suspect, a fault-tree, for a given cause. The same discernment can be achieved with a formal analysis (with parametric and nonparametric tests), perhaps more discriminating than can be accomplished by even the most trained eye, but the reasoning and the justification are much the same. (The capabilities of these techniques may be checked by simulating data deliberately generated to violate or obey the various assumptions.)