Nov.18, 1924 -April 25, 2000

Today is Lucien Le Cam’s birthday. He was an error statistician whose remarks in an article, “A Note on Metastatisics,” in a collection on foundations of statistics (Le Cam 1977)* had some influence on me. A statistician at Berkeley, Le Cam was a co-editor with Neyman of the Berkeley Symposia volumes. I hadn’t mentioned him on this blog before, so here are some snippets from EGEK (Mayo, 1996, 337-8; 350-1) that begin with a snippet from a passage from Le Cam (1977) (Here I have fleshed it out):

“One of the claims [of the Bayesian approach] is that the experiment matters little, what matters is the likelihood function after experimentation. Whether this is true, false, unacceptable or inspiring, it tends to undo what classical statisticians have been preaching for many years: think about your experiment, design it as best you can to answer specific questions, take all sorts of precautions against selection bias and your subconscious prejudices. It is only at the design stage that the statistician can help you.

Another claim is the very curious one that if one follows the neo-Bayesian theory strictly one would not randomize experiments….However, in this particular case the injunction against randomization is a typical product of a theory which ignores differences between experiments and experiences and refuses to admit that there is a difference between events which are made equiprobable by appropriate mechanisms and events which are equiprobable by virtue of ignorance. …

In spite of this the neo-Bayesian theory places randomization on some kind of limbo, and thus attempts to distract from the classical preaching that double blind randomized experiments are the only ones really convincing.

There are many other curious statements concerning confidence intervals, levels of significance, power, and so forth. These statements are only confusing to an otherwise abused public”. (Le Cam 1977, 158)

Back to EGEK:

Why does embracing the Bayesian position tend to undo what classical statisticians have been preaching? Because Bayesian and classical statisticians view the task of statistical inference very differently,

In [chapter 3, Mayo 1996] I contrasted these two conceptions of statistical inference by distinguishing evidential-relationship or E-R approaches from testing approaches, … .

The E-R view is modeled on deductive logic, only with probabilities. In the E-R view, the task of a theory of statistics is to say, for given evidence and hypotheses, how well the evidence confirms or supports hypotheses (whether absolutely or comparatively). There is, I suppose, a certain confidence and cleanness to this conception that is absent from the error-statistician’s view of things. Error statisticians eschew grand and unified schemes for relating their beliefs, preferring a hodgepodge of methods that are truly ampliative. Error statisticians appeal to statistical tools as protection from the many ways they know they can be misled by data as well as by their own beliefs and desires. The value of statistical tools for them is to develop strategies that capitalize on their knowledge of mistakes: strategies for collecting data, for efficiently checking an assortment of errors, and for communicating results in a form that promotes their extension by others.

Given the difference in aims, it is not surprising that information relevant to the Bayesian task is very different from that relevant to the task of the error statistician. In this section I want to sharpen and make more rigorous what I have already said about this distinction.

…. the secret to solving a number of problems about evidence, I hold, lies in utilizing—formally or informally—the error probabilities of the procedures generating the evidence. It was the appeal to severity (an error probability), for example, that allowed distinguishing among the well-testedness of hypotheses that fit the data equally well… .

A few pages later in a section titled “Bayesian Freedom, Bayesian Magic” (350-1):

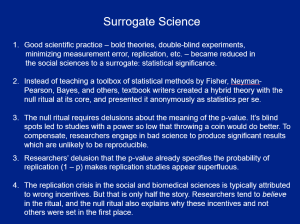

A big selling point for adopting the LP (strong likelihood principle), and with it the irrelevance of stopping rules, is that it frees us to do things that are sinful and forbidden to an error statistician.

“This irrelevance of stopping rules to statistical inference restores a simplicity and freedom to experimental design that had been lost by classical emphasis on significance levels (in the sense of Neyman and Pearson). . . . Many experimenters would like to feel free to collect data until they have either conclusively proved their point, conclusively disproved it, or run out of time, money or patience … Classical statisticians … have frowned on [this]”. (Edwards, Lindman, and Savage 1963, 239)1

Breaking loose from the grip imposed by error probabilistic requirements returns to us an appealing freedom.

Le Cam, … hits the nail on the head:

“It is characteristic of [Bayesian approaches] [2] . . . that they … tend to treat experiments and fortuitous observations alike. In fact, the main reason for their periodic return to fashion seems to be that they claim to hold the magic which permits [us] to draw conclusions from whatever data and whatever features one happens to notice”. (Le Cam 1977, 145)

In contrast, the error probability assurances go out the window if you are allowed to change the experiment as you go along. Repeated tests of significance (or sequential trials) are permitted, are even desirable for the error statistician; but a penalty must be paid for perseverance—for optional stopping. Before-trial planning stipulates how to select a small enough significance level to be on the lookout for at each trial so that the overall significance level is still low. …. Wearing our error probability glasses—glasses that compel us to see how certain procedures alter error probability characteristics of tests—we are forced to say, with Armitage, that “Thou shalt be misled if thou dost not know that” the data resulted from the try and try again stopping rule. To avoid having a high probability of following false leads, the error statistician must scrupulously follow a specified experimental plan. But that is because we hold that error probabilities of the procedure alter what the data are saying—whereas Bayesians do not. The Bayesian is permitted the luxury of optional stopping and has nothing to worry about. The Bayesians hold the magic.

Or is it voodoo statistics?

When I sent him a note, saying his work had inspired me, he modestly responded that he doubted he could have had all that much of an impact.

_____________

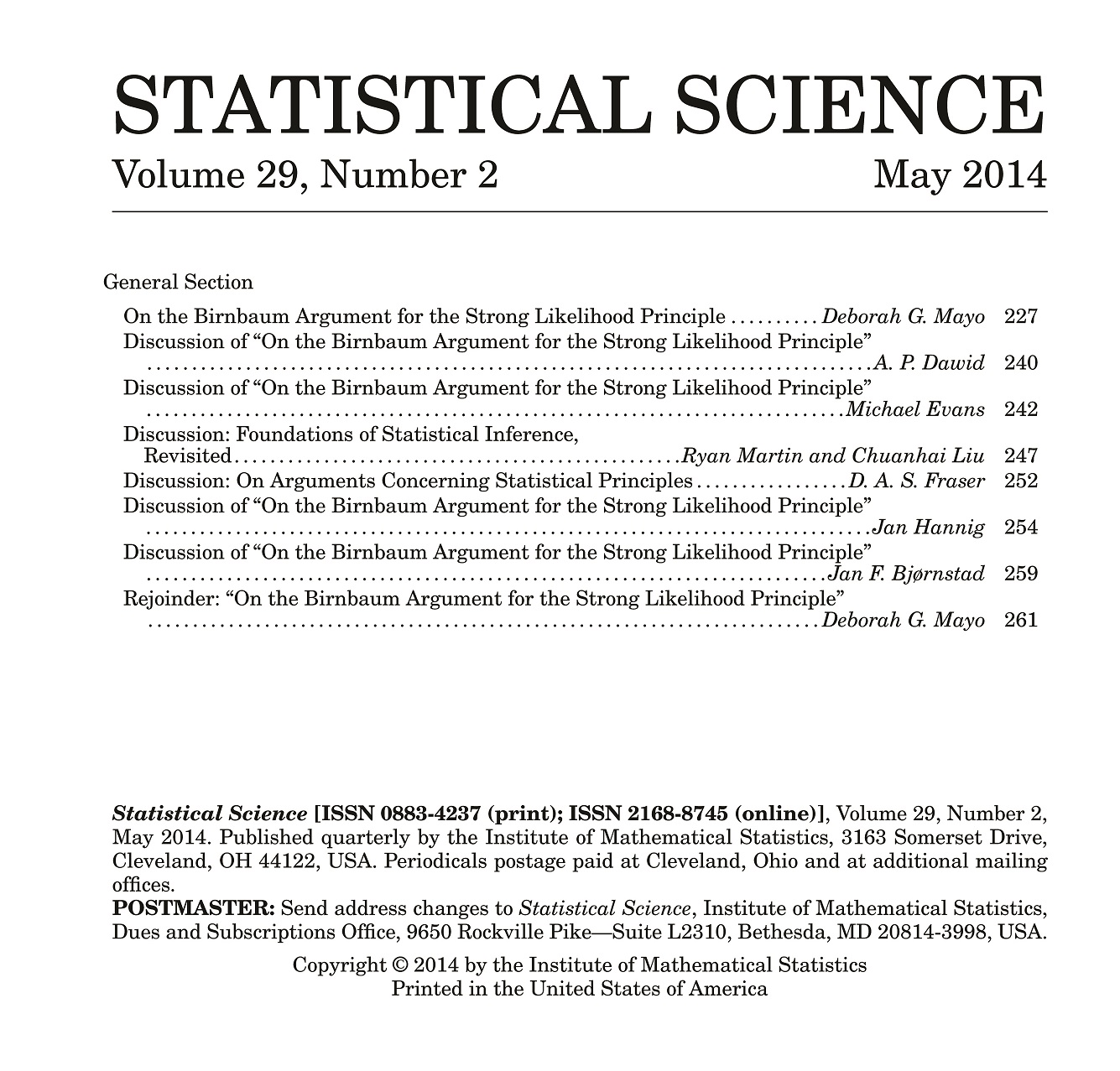

*I had forgotten that this Synthese (1977) volume on foundations of probability and statistics is the one dedicated to the memory of Allan Birnbaum after his suicide: “By publishing this special issue we wish to pay homage to professor Birnbaum’s penetrating and stimulating work on the foundations of statistics” (Editorial Introduction). In fact, I somehow had misremembered it as being in a Harper and Hooker volume from 1976. The Synthese volume contains papers by Giere, Birnbaum, Lindley, Pratt, Smith, Kyburg, Neyman, Le Cam, and Kiefer.

REFERENCES:

Armitage, P. (1961). Contribution to discussion in Consistency in statistical inference and decision, by C. A. B. Smith. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society (B) 23:1-37.

_______(1962). Contribution to discussion in The foundations of statistical inference, edited by L. Savage. London: Methuen.

_______(1975). Sequential Medical Trials. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Edwards, W., H. Lindman & L. Savage (1963) Bayesian statistical inference for psychological research. Psychological Review 70: 193-242.

Le Cam, L. (1974). J. Neyman: on the occasion of his 80th birthday. Annals of Statistics, Vol. 2, No. 3 , pp. vii-xiii, (with E.L. Lehmann).

Le Cam, L. (1977). A note on metastatistics or “An essay toward stating a problem in the doctrine of chances.” Synthese 36: 133-60.

Le Cam, L. (1982). A remark on empirical measures in Festschrift in the honor of E. Lehmann. P. Bickel, K. Doksum & J. L. Hodges, Jr. eds., Wadsworth pp. 305-327.

Le Cam, L. (1986). The central limit theorem around 1935. Statistical Science, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 78-96.

Le Cam, L. (1988) Discussion of “The Likelihood Principle,” by J. O. Berger and R. L. Wolpert. IMS Lecture Notes Monogr. Ser. 6 182–185. IMS, Hayward, CA

Le Cam, L. (1996) Comparison of experiments: A short review. In Statistics, Probability and Game Theory. Papers in Honor of David Blackwell 127–138. IMS, Hayward, CA.

Le Cam, L., J. Neyman and E. L. Scott (Eds). (1973). Proceedings of the Sixth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Vol. l: Theory of Statistics, Vol. 2: Probability Theory, Vol. 3: Probability Theory. Univ. of Calif. Press, Berkeley Los Angeles.

Mayo, D. (1996). [EGEK] Error Statistics and the Growth of Experimental Knowledge. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Chapter 10; Chapter 3)

Neyman, J. and L. Le Cam (Eds). (1967). Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Vol. I: Statistics, Vol. II: Probability Part I & Part II. Univ. of Calif. Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

[1] For some links on optional stopping on this blog: Highly probably vs highly probed: Bayesian/error statistical differences.; Who is allowed to cheat? I.J. Good and that after dinner comedy hour….; New Summary; Mayo: (section 7) “StatSci and PhilSci: part 2″; After dinner Bayesian comedy hour….; Search for more, if interested.

[2] Le Cam is alluding mostly to Savage, and (what he called) the “neo-Bayesian” accounts.