Phil 6334* Day #4: Mayo slides follow the comments below. (Make-up for Feb 13 snow day.) Popper reading is from Conjectures and Refutations.

As is typical in rereading any deep philosopher, I discover (or rediscover) different morsals of clues to understanding—whether fully intended by the philosopher or a byproduct of their other insights, and a more contemporary reading. So it is with Popper. A couple of key ideas to emerge from Monday’s (make-up) class and the seminar discussion (my slides are below):

- Unlike the “naïve” empiricists of the day, Popper recognized that observations are not just given unproblematically, but also require an interpretation, an interest, a point of view, a problem. What came first, a hypothesis or an observation? Another hypothesis, if only at a lower level, says Popper. He draws the contrast with Wittgenstein’s “verificationism”. In typical positivist style, the verificationist sees observations as the given “atoms,” and other knowledge is built up out of truth functional operations on those atoms.[1] However, scientific generalizations beyond the given observations cannot be so deduced, hence the traditional philosophical problem of induction isn’t solvable. One is left trying to build a formal “inductive logic” (generally deductive affairs, ironically) that is thought to capture intuitions about scientific inference (a largely degenerating program). The formal probabilists, as well as philosophical Bayesianism, may be seen as descendants of the logical positivists–instrumentalists, verificationists, operationalists (and the corresponding “isms”). So understanding Popper throws a lot of light on current day philosophy of probability and statistics.

- The fact that observations must be interpreted opens the door to interpretations that prejudge the construal of data. With enough interpretive latitude, anything (or practically anything) that is observed can be interpreted as in sync with a general claim H. (Once you opened your eyes, you see confirmations everywhere, as with a gestalt conversion, as Popper put it.) For Popper, positive instances of a general claim H, i.e., observations that agree with or “fit” H, do not even count as evidence for H if virtually any result could be interpreted as according with H.

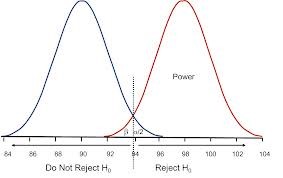

Note a modification of Popper here: Instead of putting the “riskiness” on H itself, it is the method of assessment or testing that bears the burden of showing that something (ideally quite a lot) has been done in order to scrutinize the way the data were interpreted (to avoid “verification bias”). The scrutiny needs to ensure that it would be difficult (rather than easy) to get an accordance between data x and H (as strong as the one obtained) if H were false (or specifiably flawed). Continue reading